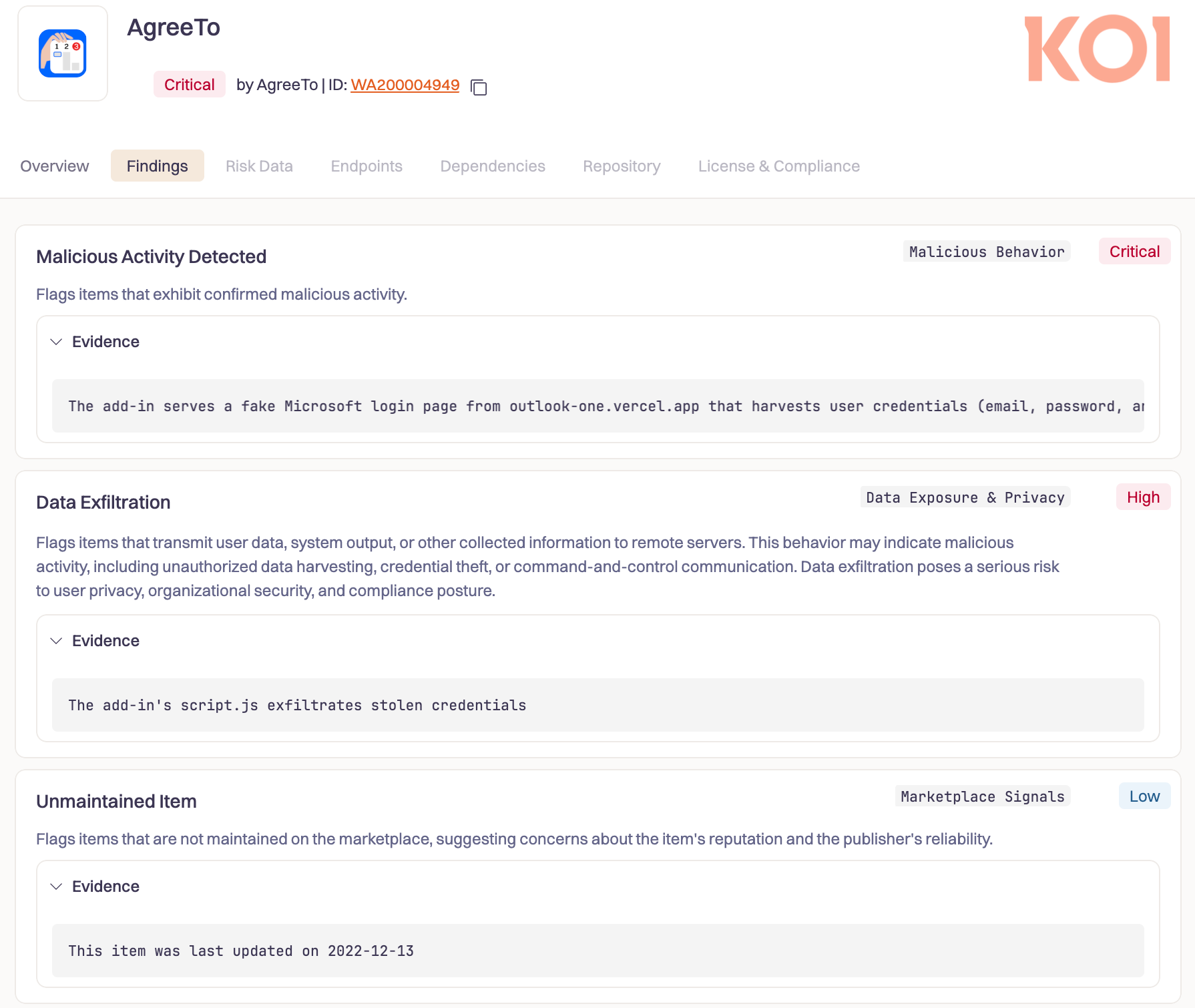

This is the first known malicious Microsoft Outlook add-in detected in the wild. But the developer who built it isn't the attacker.

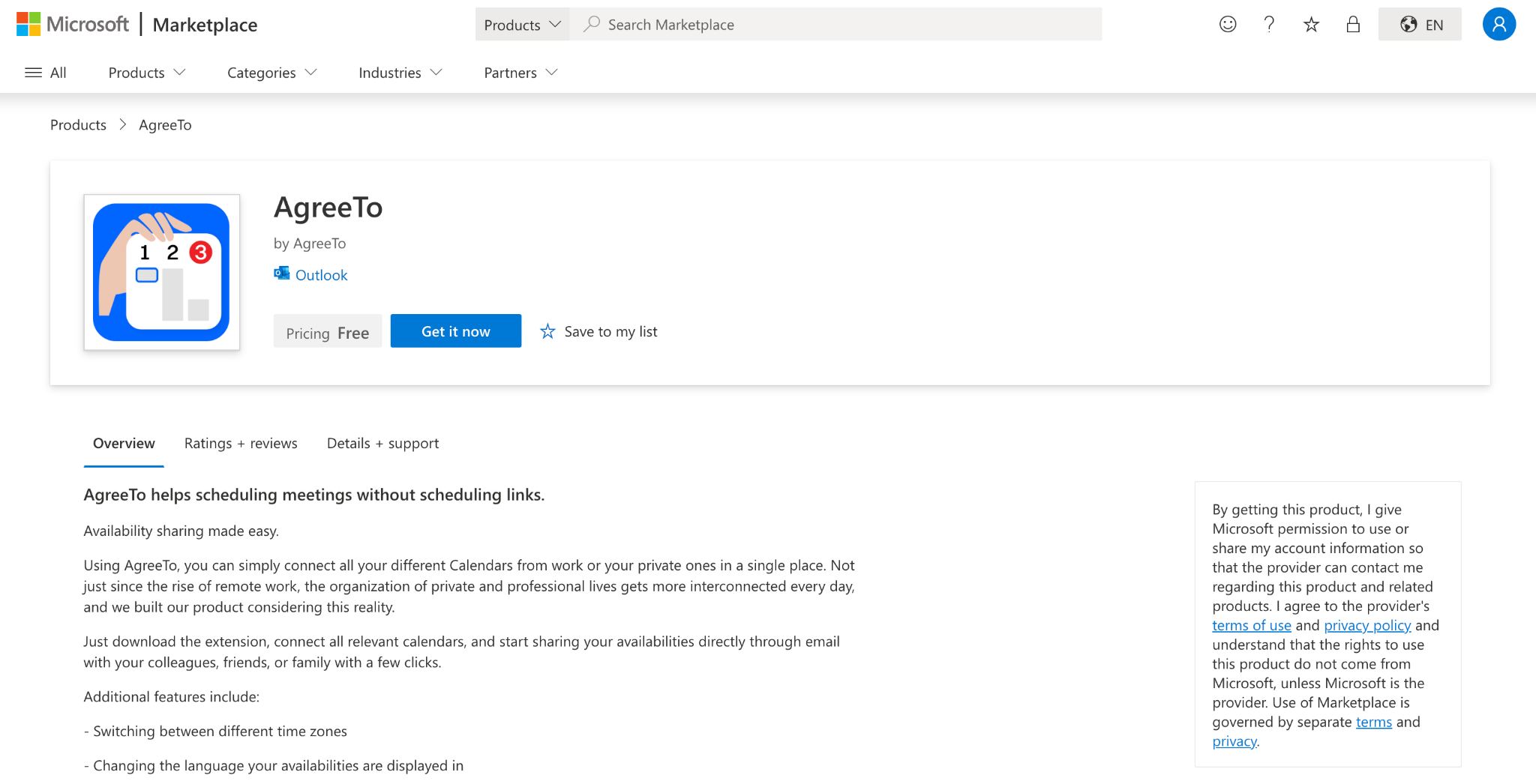

In 2022, a developer built a meeting scheduling tool called AgreeTo and published it to the Microsoft Office Add-in Store. It worked. People liked it. Then the developer moved on, and the project died.

The add-in stayed listed in Microsoft's store. The URL it pointed to - hosted on Vercel - became claimable. An attacker claimed it, deployed a phishing kit, and Microsoft's own infrastructure started serving it inside Outlook's sidebar. By gaining access to the attacker's exfiltration channel, we were able to recover the full scope of the operation: over 4,000 stolen Microsoft account credentials, credit card numbers, and banking security answers. The attacker was actively testing stolen credentials yesterday. The infrastructure is live as you read this.

This is the story of how a dead side project became a phishing weapon. It starts with how Office add-ins work.

How Office Add-Ins Work (and Why That's a Problem)

Office add-ins aren't installed code. They're URLs.

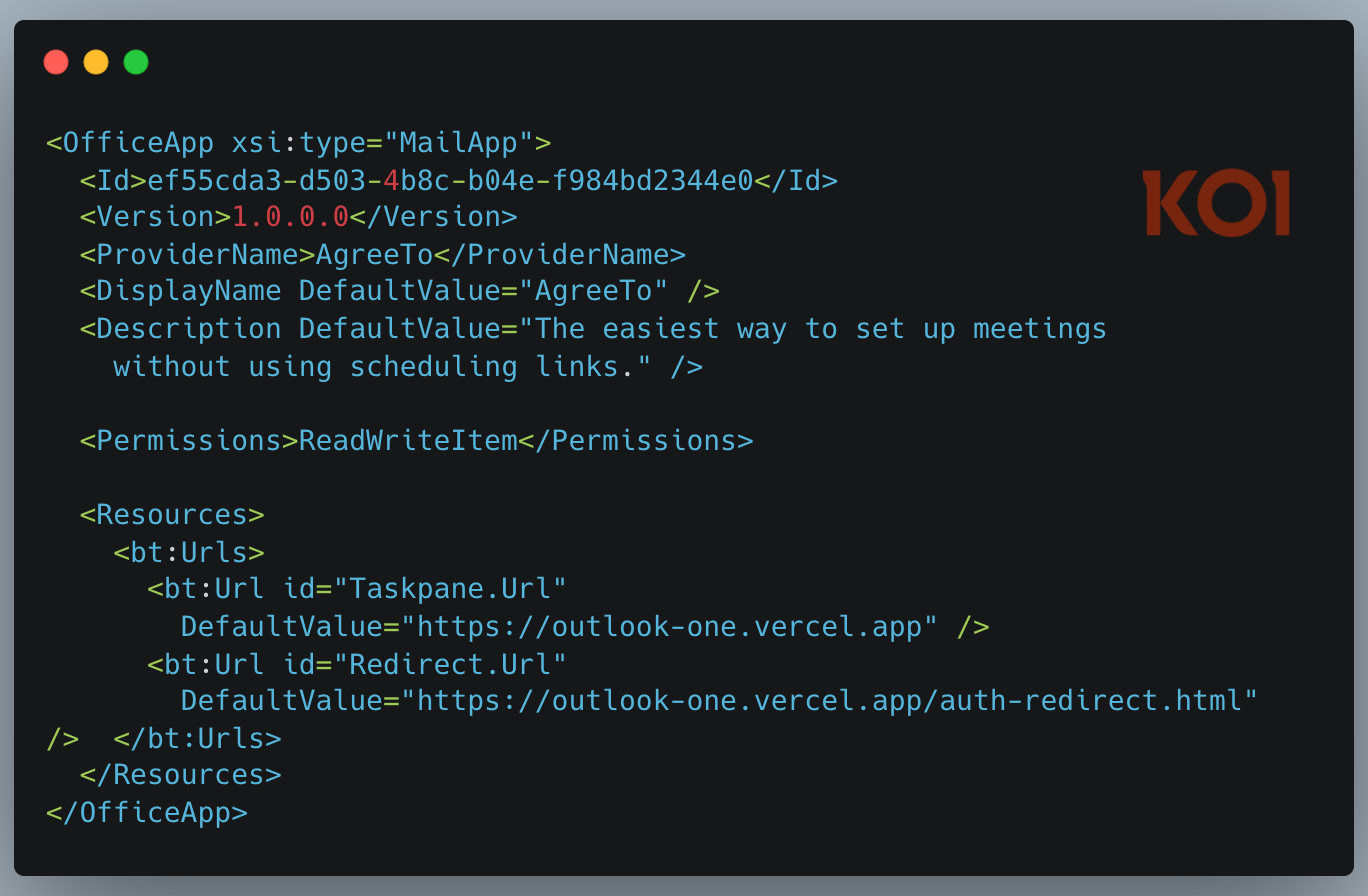

A developer submits a manifest to Microsoft - an XML file that says "load this URL in an iframe inside Outlook." Microsoft reviews the manifest, signs it, and lists the add-in in their store. But the actual content - the UI, the logic, everything the user interacts with - is fetched live from the developer's server every time the add-in opens.

Here's what that looks like. This is the manifest Microsoft signed for AgreeTo in December 2022:

Note the ReadWriteItem permission. That grants the add-in the ability to read and modify the user's emails. It was appropriate for a meeting scheduler. It's less appropriate for whoever controls that URL today.

There's no static bundle to audit. No hash to verify. Whatever outlook-one.vercel.app serves right now is what runs inside Outlook. If the developer pushes a bad update, it's live immediately. If someone else takes control of that URL, they control what every user of that add-in sees - inside Outlook's trusted sidebar, with full read and write access to their email.

Microsoft blessed this manifest once, in December 2022. They never check what the URL serves again.

Built, Loved, Abandoned

AgreeTo was a real product. An open-source meeting scheduling tool with a Chrome extension (1,000 users, 4.71-star rating, 21 reviews) and an Outlook add-in published to Microsoft's store in December 2022. The developer maintained an active GitHub repo - a full TypeScript monorepo with Microsoft Graph API integration, Google Calendar support, and Stripe billing. This was someone building a business.

Then development stopped. The last Chrome extension update shipped in May 2023. The developer's domain, agreeto.app, expired. By July 2024, users were leaving reviews on the Chrome extension:

"It was all 5 stars for me until this morning. I tried to log in, and the agreeto.app website is expired. Did this app die? I hope not."

"Did this app die? No longer works. Makes you login and goes to a GoDaddy holding page. I use this app all the time and does exactly what I need to do."

Google eventually removed the dead Chrome extension in February 2025. But the Outlook add-in stayed listed in Microsoft's Office Store, still pointing to a Vercel URL that no longer belonged to anyone.

The Takeover

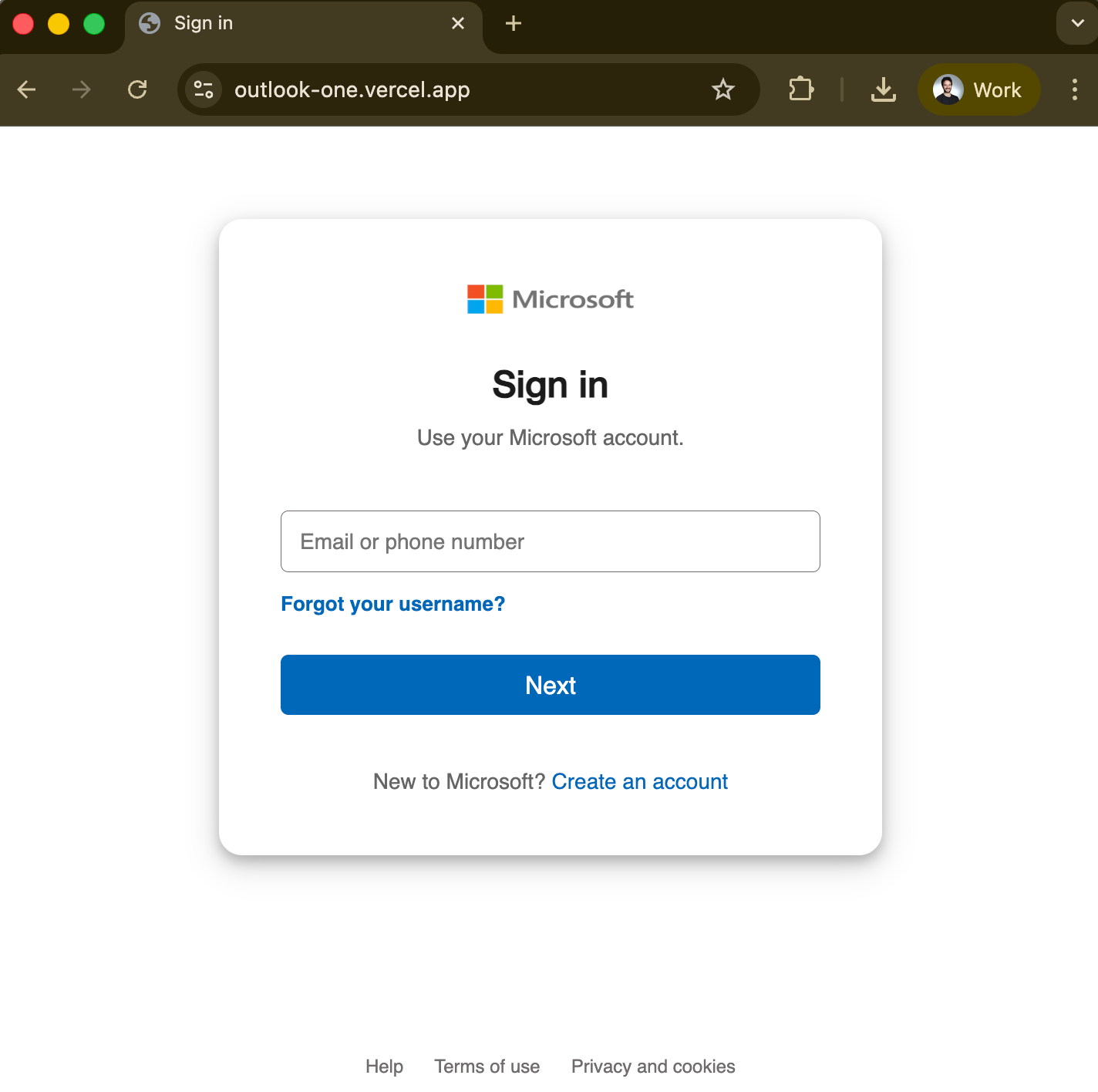

At some point after the developer abandoned the project, their Vercel deployment was deleted. The subdomain outlook-one.vercel.app became claimable. An attacker grabbed it.

They deployed a four-page phishing kit: a fake Microsoft sign-in page, a password collection page, an exfiltration script, and a redirect. That's all it took.

They didn't submit anything to Microsoft. They weren't required to pass any review. They didn't create a store listing. The listing already existed - Microsoft-reviewed, Microsoft-signed, Microsoft-distributed. The attacker just claimed an orphaned URL, and Microsoft's infrastructure did the rest.

The fingerprints of two different authors are visible across the infrastructure. The original developer's assets - icons, OAuth handlers, Microsoft design files - are all 404. The attacker didn't recreate them because they didn't have the source code. They only deployed what they needed: the phishing flow.

The Attack

When a victim opens the AgreeTo add-in in Outlook, they don't see a meeting scheduler. They see a Microsoft sign-in page.

They enter their email, then their password. A single JavaScript function collects the credentials along with the victim's IP address, and sends everything to the attacker via Telegram's Bot API. No command-and-control servers. No complex infrastructure. Just a fetch() call to Telegram.

Then a loading spinner for a few seconds, and a seamless redirect to the real login.microsoftonline.com. The victim assumes they need to sign in again and goes about their day. They have no idea their password was just stolen.

The phishing technique itself is basic. What makes it effective is the context: it's running inside Outlook, delivered by Microsoft's own add-in infrastructure, behind a trusted permission prompt.

The Scale

Microsoft's Office Add-in Store doesn't display installation counts, so there was no way to assess the impact from the listing alone.

But the attacker made a critical mistake. Their exfiltration infrastructure was poorly secured, and we were able to get inside it. First, we confirmed the scale of the operation: over 4,000 victims. Then we went further. We wrote a script to recover the full contents of every stolen credential the attacker had collected. We ran it overnight. By morning, we had the complete dataset - every email, every password, every credit card number, every intercepted security answer. The full scope of the damage, laid out in front of us.

Holding the victim data meant we could do something about it: notify the compromised users and report the infrastructure for takedown.

The campaign is still active. New victims are being compromised by the hour.

What we found went far beyond the Outlook add-in. The same attacker operates at least 12 distinct phishing kits, each impersonating a different brand - Canadian ISPs, banks, webmail providers. The stolen data included not just email credentials but credit card numbers, CVVs, PINs, and banking security answers used to intercept Interac e-Transfer payments. This is a professional, multi-brand phishing operation. The Outlook add-in was just one of its distribution channels.

The Structural Problem

What makes this case significant isn't the phishing technique - a fake login page and a Telegram bot are about as basic as it gets. What's significant is the delivery mechanism and the structural failure that enabled it.

The attacker didn't send a phishing email. They didn't need to trick someone into clicking a suspicious link. They took over an abandoned URL that Microsoft's own infrastructure was pointing users to - and Microsoft kept distributing it, inside Outlook, behind a trusted permission prompt.

For existing security tooling, this is nearly invisible:

- Email security gateways won't catch it - the phishing page doesn't arrive via email.

- Endpoint protection won't flag it - it's JavaScript running inside a legitimate Microsoft process.

- URL filtering miss it - the phishing pages are hosted on vercel.app, which serves millions of legitimate applications.

But the deeper problem is architectural. Office add-ins are remote dynamic dependencies - they load a URL in an iframe. The content is mutable. An add-in that's clean on Monday can serve a phishing page on Tuesday - or, as in this case, years later. Microsoft reviews the manifest at submission, but the actual content can change at any time without further review.

And it could have been worse. The AgreeTo manifest declares ReadWriteItem permissions - the add-in can read and modify the user's emails. The attacker used it for a simple phishing page, but nothing stops them from deploying JavaScript that silently reads the victim's inbox, exfiltrates sensitive messages, or sends phishing emails from the victim's own account. The permission was granted by Microsoft when the add-in was legitimate. It still applies now that it's not.

Final Thoughts

None of this is a new concern. Security researchers at MDSec flagged Office add-ins as an attack surface back in 2019, demonstrating how they could be weaponized to gain persistent access to a victim's mailbox. Their post ended with a warning: "Microsoft also allow developers to push these add-ins to a store, where users can install them. I'm sure you can see the potential problem there." Seven years later, AgreeTo is exactly the scenario they predicted.

Office add-ins are remote dynamic dependencies - their content can change at any time, making point-in-time audits insufficient. Koi continuously monitors and audits self-provisioned software across every marketplace - including browser extensions, IDE plugins, Office add-ins, and more - so that when an add-in turns malicious, you know about it before your users do. Book a demo to see how.

IOCs

outlook-one.vercel[.]app- Phishing domain (LIVE)WA200004949- Office Add-in ID

We have reported this add-in to Microsoft for removal from the Office Add-in Store, submitted an abuse report to Vercel for outlook-one.vercel.app, and filed Telegram abuse reports for both the bot and the operator account. Affected victims whose credentials were found in the bot's message history have been notified where possible.

%20copy.jpg)