Most of the time, when you install software, you don’t think twice about it. The files get downloaded over HTTPS. The checksums are verified. Everything’s secure - or at least, that’s the assumption.

And thank god for that. If every download could be intercepted, or every binary replaced without warning, the internet would be a minefield.

But what if both protections were missing? What if the download was served over plain HTTP, and the installer wasn’t even validated after the fact? Come on - it's 2025! That can’t still happen in a widely used package manager. r..right?

Except… that’s exactly what can happen inside Homebrew’s core cask system. We found 20 casks in Homebrew's official tap that are vulnerable to trivial man-in-the-middle attacks - no exploit required, no elevated permissions needed. These packages download over unencrypted HTTP with no integrity verification, meaning anyone on the network path can swap the payload for malware.

These aren't obscure packages. They're sitting in the core tap - the same trusted source that serves Chrome, Spotify, and thousands of other apps to millions of developers every day.

We didn't just theorize about this. We intercepted an install, swapped in a malicious .dmg, and watched Homebrew drop it straight into /Applications without a single warning.

Background: How Homebrew Casks Work

To fully understand the implications of this vulnerability, you first need to understand how Homebrew’s cask system works under the hood.

Most people think of Homebrew as the go-to command line package manager for installing developer tools on MacOS (brew install python, brew install git, etc.). That’s the core - the Homebrew formulae, where packages are typically built from source or distributed as binaries.

But when you want to install actual macOS applications - .dmgs, .pkgs, and app bundles - you switch over to the cask side of Homebrew (brew install --cask). This system handles downloading and installing GUI apps, handling the messy stuff like dragging icons to /Applications or clicking through installers, all automatically.

Who Maintains All This?

Here’s where it gets interesting. Homebrew is massive, but it’s fundamentally community-driven.

The main tap, homebrew/homebrew-cask, is maintained on GitHub. Anyone can submit a new cask or update an existing one by making a pull request - contributors propose changes, maintainers review them, and once approved, those updates go live for every Homebrew user worldwide.

On top of that, users can add third-party taps - external GitHub repositories with their own sets of casks or formulae. These third-party taps don’t go through the same level of oversight as the official taps, which makes them an even riskier playground if you’re not careful. If a malicious or poorly maintained third-party tap slips through, you’ve got a whole new set of attack surfaces.

But let's focus specifically on the official homebrew/homebrew-cask tap - the mainline, trusted source - because even here, the risks are very real.

What Happens When You Install a Cask?

Let’s break down the flow.

When you run:

brew install --cask some-app

Homebrew:

1. Parses the cask formula - pulling metadata like the download URL, version, and checksum.

2. Fetches the installer - typically a .dmg or .pkg - straight from the url defined in the cask.

3. (Maybe) validates the checksum - but here’s where it gets tricky.

Why Does no_check Exist?

In theory, Homebrew verifies the checksum (sha256) of the downloaded file to ensure it hasn’t been tampered with. But many casks - especially ones that auto-update or serve dynamic, versionless URLs - use the no_check flag to skip this validation. Why? Because in these cases, the checksum can change frequently, making it impractical (or even impossible) to maintain a fixed hash in the cask formula. It’s not just about convenience or cutting corners - sometimes, it’s a necessary tradeoff to allow Homebrew to install fast-moving, constantly updated apps.

In fact, in the main official cask tap alone, there are over 2,800 casks that explicitly declare sha256 :no_check. But skipping that integrity check opens a giant hole in the trust chain, especially when paired with an unencrypted connection.

This isn’t some niche corner of the ecosystem. We’re talking about widely used apps - here’s a taste:

- Google Chrome (

google-chrome) → over 260K installs this year - Spotify (

spotify) → over 90K installs this year - Steam (

steam) → over 35K installs this year - Google Drive (

google-drive) → over 25K installs this year

Now, no_check alone isn't necessarily a disaster. Many major applications - including the popular casks we just listed - still serve their downloads over secure HTTPS connections. In those cases, even without a checksum, the encrypted transport layer protects the payload from tampering in transit.

The real problem emerges when no_check is combined with HTTP. No integrity verification, no transport encryption - just a direct, unprotected pipe from a remote server to your /Applications folder. Anyone positioned on the network path (think public WiFi, compromised routers, or malicious ISPs) can intercept the download and swap in whatever they want.

So how common is this combination? We dug into the official homebrew-cask tap and found 20 casks that serve downloads over plain HTTP with no_check enabled. That's 20 open doors in the core tap - the trusted source that developers rely on every day.

What Do We Assume Is Safe?

The trust model behind Homebrew casks leans on a few critical assumptions:

✅ That the upstream server defined in the url is legitimate and hasn’t been compromised.

✅ That the transport layer (ideally HTTPS) protects the download from tampering.

✅ That Homebrew itself will validate the integrity of the downloaded file.

Individually, each of these gaps might be survivable. But when you combine both - tampering with the payload (via unencrypted downloads or a compromised server) and disabled checksum verification - you create the perfect conditions for a seamless, undetectable attack. And that’s exactly where this vulnerability lives.

Proof of Concept (PoC): Hijacking a Homebrew Cask Install

To demonstrate just how dangerous the combination of no_check and HTTP can be, we put together a simple proof of concept.

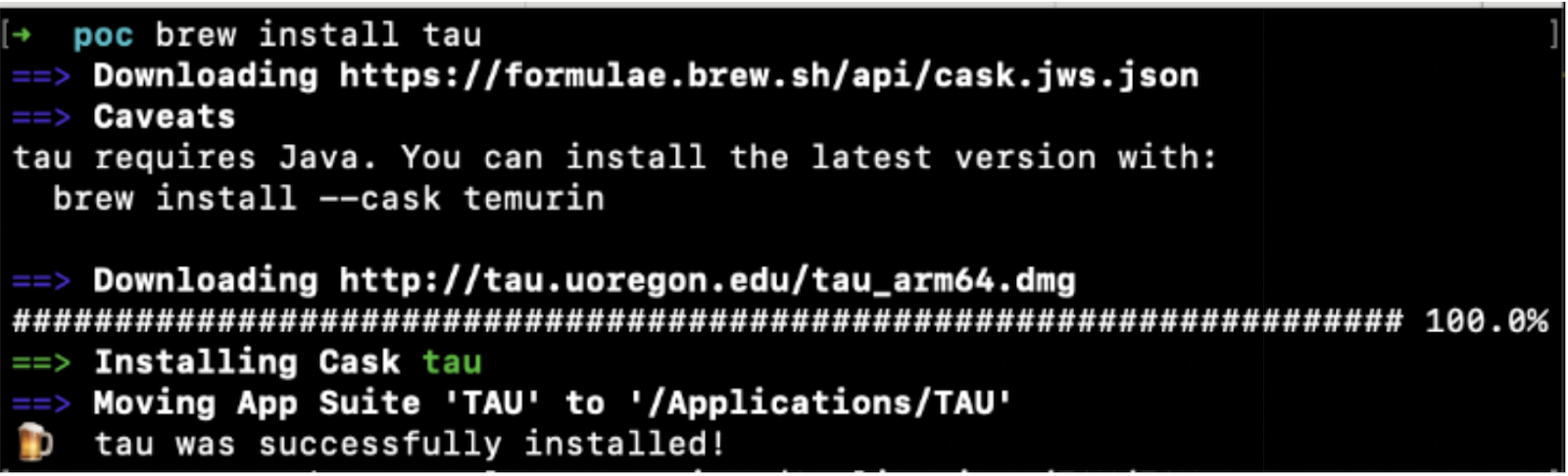

We targeted the tau cask, which fetches its installer over HTTP and has checksum validation disabled. On the surface, it’s just another package install - but under the hood, it becomes a perfect attack vector for a MITM interception.

Step 0: Preparing the Attack

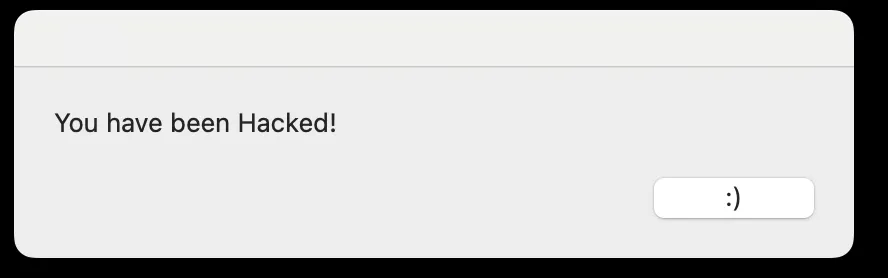

Before launching the attack, we first created a “malicious” .dmg file - in this case, a simple app designed to pop up a harmless message saying “You have been hacked!” when opened. This was purely for demonstration purposes, but it proves that the payload can be fully replaced.

We also set up our position in the network to perform a Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) interception, allowing us to catch and replace HTTP traffic between the victim’s machine and the upstream server.

Step 1: Running the Install

Running the standard Homebrew install command:

In the terminal output, you can clearly see:

- Homebrew reaches out to the upstream source:

http://tau.uoregon.edu/tau_arm64.dmg - There’s no SHA256 check happening (

no_checkis set in the cask formula).

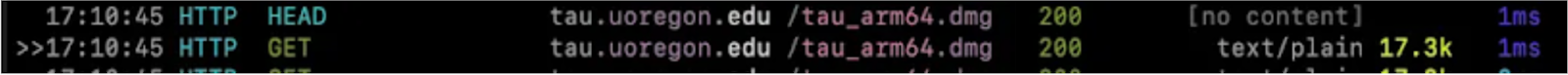

Using our access to the transport layer, we intercepted the request to the upstream server and responded on its behalf with our crafted ‘malicious’ application:

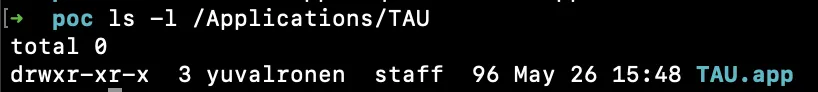

Step 2: Dropping the App in Applications

After the download, Homebrew moves the app into /Applications:

Step 3: Triggering the Malicious Payload

After the install, when the user launches the app, they’re unknowingly running the malicious payload we swapped in during the MITM attack. In this PoC, that resulted in a simple pop-up message:

This wasn’t some lab-only, theoretical test. This was a real-world, repeatable demonstration where:

✅ The installer was fetched over insecure HTTP.

✅ The cask formula used no_check, skipping integrity verification.

✅ Homebrew installed and placed the app, just as it was designed to do.

By sitting on the network path, we were able to seamlessly inject a malicious app into the user’s system - no prompts, no alerts, no elevated permissions required.

Keep the Tap Clean

The Homebrew cask ecosystem wasn’t built for attackers - it was built for convenience. But as with any convenience layer, cracks appear when assumptions go unexamined. With thousands of apps, community-maintained casks, and formulae pulled from upstream sources, it’s easy to forget just how much trust is baked into every brew install --cask command.

This proof of concept reveals something deeper than just a misconfiguration. It exposes a structural weakness: a system that quietly allows integrity checks to be bypassed and insecure transport to slip through. On their own, these factors might raise eyebrows. Combined, they create an unmonitored pathway for delivering malicious code directly to the user’s machine - bypassing the usual defenses, sidestepping permissions, and embedding malware under the cover of a trusted install process.

Today, there are already 20 casks in the official tap that combine no_check and HTTP - each one a potential open door for attackers. It's a clear sign that the ecosystem's security assumptions need to evolve. Teams, maintainers, and individual users need to rethink how they manage and audit casks - tightening controls, enforcing HTTPS, and minimizing the use of no_check. Without that, the growing complexity of the cask system risks turning a beloved developer tool into an attacker's delivery pipeline.

This is exactly the kind of blind spot Koi is built to catch. Our platform continuously monitors software delivery pipelines - package managers, browser extensions, IDE extensions - flagging risky combinations like missing checksums and insecure transport before they become attack vectors. If your team had been running Koi, these 20 vulnerable casks would have been flagged the moment they appeared in your environment, and blocked before the payload ever touched the disk.

As software ecosystems grow more dynamic and decentralized, these overlooked trust gaps will only multiply. If you're relying on package managers to keep your endpoints clean, it's time to add deeper visibility into what's really flowing through your install commands.

Talk to us about how we can help secure your environment.